** Update: 3/20/23, this case was settled a few days ago. We don’t know the terms and can’t read too much into it. The Weeknd has excellent counsel, as you would expect, so although I think everything I outlined in this analysis a couple of years ago makes perfect sense, we don’t get to know why or how it was settled. Feel free to comment. Here’s the post from Sept 2021.

————————————————————–

The Weekend (Weeknd) is getting sued for copyright infringement. Yes, again. This time by a pair of composer/producers named Suniel Fox and Henry Strange, collectively “Epikker” (awesome name), who think “Call Out My Name” was plagiarized from their track, “Vibeking.” And let me just add, Fox and Strange sued everyone involved. I think it’s the longest list of “defendants” I’ve ever seen.

“Call Out My Name” was a pretty big hit, and you probably know it, but here it is just in case:

Listen to the first twenty seconds or sit through the whole thing. It just grooves over the same four bars over and over.

And as for “Vibeking” which The Weeknd allegedly copied, I can’t even find it anywhere on the internet. I’ll keep looking. (If you find it, by all means, do tell me where.) We dont really need it. Seriously. We don’t.

We have the complaint itself which sets things out, vaguely, as this: “quantitatively and qualitatively similar material in their respective lead guitar and vocal hooks, including melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic elements.” And thankfully they also wrote out some actual notes and made some specific claims which we do assume are musicologically accurate, as far as that goes.

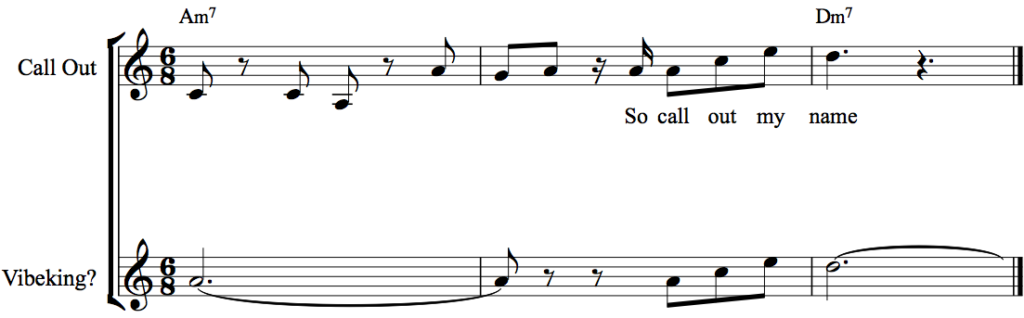

It does not go very far. But let’s assume that indeed their song goes just as they say it goes. If I understand them correctly, this is the side-by-side transcription (mine) of both melodies, illustrating the key similarities they’d like us to know about.

Here’s what those notes tell us, and these are some of the observations stressed in the complaint:

I take it, from having read the complaint, that there are no lyrics to “Vibeking,” and if there are, nothing is sung to this particular melody, because otherwise, they would so state. When they claim “quantitatively and qualitatively similar material in their respective lead guitar and vocal hooks,” we can surmise the notes they’re offering from “Vibeking” must be a guitar part and the “vocal hooks” to which they refer are only The Weeknd’s. So we’re talking about just a guitar part that occurs ten times in “Vibeking.” There are evidently no vocal hooks in Vibeking that appear in Call Out My Name. And moreover, I take it the guitar part isn’t precisely this throughout the tune so much as kinda like this. They footnote:

“There are occasional variations within those ten occurrences, whereby the hook is embellished with interim scale degrees on the sustained tones.”

And maybe that’s perfectly reasonable, but it’s probably weakening.

You can’t copy another’s work unless you’ve heard it. And again, I can’t find a copy of “Vibeking” anywhere, which suggests that if The Weeknd had access to “Vibeking,” he would need to have gotten a demo or something. And indeed that’s the story the complaint tells — the producers of “Vibeking” sent “Vibeking” to people who collaborate with The Weeknd. There’s a short version account of the story on the Complete Music Update site. Or you can read the long version, the complaint itself.

Let’s say, for the heck of it, that The Weeknd may have heard “Vibeking” at some point, and over time forgot where he’d heard it. Or better yet, let’s say he didn’t forget and set out to write a song with a similar vibe. The plaintiffs could still run into issues around “originality,” and substantial similarity.

Both of these songs just vibe back and forth between two chords, right? — the i chord and the iv chord; the “one” and the “four,” the tonic and the subdominant. And the complaint reads: “This minimalistic harmonic variation is a distinctive compositional element of VIBEKING.” That’s a nice way of saying it’s just two chords back and forth. Fine, call it “distinctive minimalism.” But if, as they say, “you can’t copyright a chord progression,” which is true for the most part, you sure as heck can’t copyright one that just goes back and forth between THE most obviously available chord and the third most obviously available chord. Amen I say to anyone who will get the joke.

And the “variation” of these two ‘distinctive’ chords? “Call Out My Name” inherits those two chords from the recording it samples, “Killing Time” by Nicolas Jaar, into which I’m now going to drop you at the three-minute thirty mark:

“Killing Time” came out in 2016. The complaint claims that while “Vibeking” was first published in 2017, it was actually created in 2015. So I suppose they could be saying “Killing Time” is a copy of “Vibeking” too?

Forensic musicologists are asked to look for probative value in observable similarities. This is partly a probability exercise. So I ask you, what’s more probable, that the Weeknd set out to copy Vibeking and combed through stacks till he found an ethereal loop that went back and forth between the two chords he loves so much from “Vibeking,” or that a cow jumps over the moon?

“Sure,” you say, “but what, Mr. Musicologist, about those four (4) notes that are exactly the same? The ones to which The Weeknd sings “Call Out My Name?”

What? Do you mean, these notes?

That’s “Still Got The Blues” from the late and great “Gary Moore.” He plays that four-note figure to transition between the same chords in the same 6/8 time like a gazillion times in this tune. It’s from 1990.

And even if he hadn’t, countless others have. There’s nothing very distinctive about this four-note melodic figure. Here’s how mundane it is: (Remember, the songs pretty much go back and forth on just two chords. In our transposition, A minor and D minor. Ignore the “seventh” thing for now; it’s not especially relevant.)

In other words, that melody is, I’d say, comprised of the most automatically selected note, followed by the next two most automatic, then as the harmony changes to the other of the two chords, we get the most automatic note possible.

Okay, we can quibble over what notes are actually “the most automatic,” but take the point! Copyright expressly doesn’t protect scales, chords, or arpeggios — they’re the building blocks of music, shared by all creators. When arpeggios become melody, as here, then they become more protectable, but a four-note musical phrase should probably not be.

This. has. no. shot.

Wanna argue with me? Have at it. I’m on Twitter.

5 Comments

Really good article. Wasn’t expecting to find anything on this. Still can’t find Vibeking

Lawsuit was settled. Makes you wonder if they thought it had merit despite it seeming not to?

The settlement could’ve been rationalized any number of ways apart from merit.

A lot of what you say makes sense, but the fact remains that they sent their song to him and he used parts of it without permission or giving credit- however simple/basic the chord progressions may be.

Hi Allondra,

The fact may or may not be that they sent their song. Certainly he may or may not have ever heard it. And ultimately what I’m saying is even if it were true, it wouldn’t matter. That musical idea alone is not theirs to protect. It is, on its own, too brief, too simple, and too common to be owned by the plaintiff, the defendant, you, me or anyone.